Her story #20 - aida

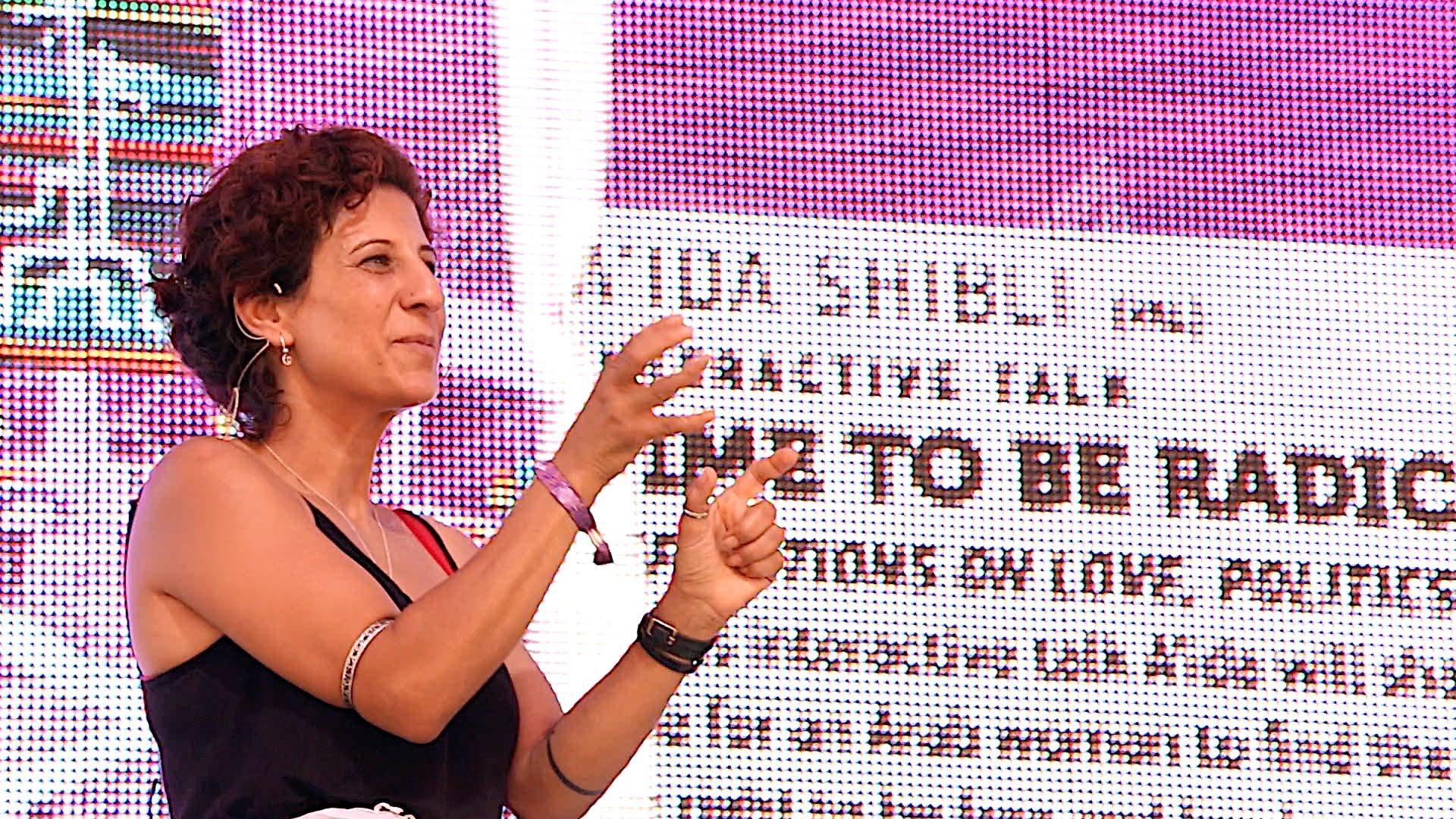

Aida speaking at Boom Festival 2014 in Portugal about political activism

Tamera

I am a Palestinian Bedouin from Shibli, a village next to Mount Tabor in the North, between Nazareth and Tiberias. I have lived in Portugal since 2007, and my reason for moving to Portugal is a long story.

Back around the Second Intifada, I was a nurse at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem and pregnant at the same time, abandoned by my former husband. It was a very traumatic period for me, on the personal level and the political level as well. I have been a political and social activist for many years, and I wanted to find ways to get rid of the occupation with non-violent solutions. I realized that the whole way we live needs to be changed and asked myself: How can this come about? How do other people live differently?

At the time I became acquainted with a project in Portugal called Peace Research Village or Tamera, which made me curious, but I eventually left it, because I was too busy raising a child and living in Jerusalem as a mother. A couple of years later I attended a conference about peace, and by chance someone from the village was there too and approached me. I told him that I didn't have much time to take part in this project. I ended up joining them two years later.

I was surprised by, how the village was formed, and how what I had thought about for a long time actually existed.

I grew a relationship with the place, and I began collaborating with it. We had Palestinians come and learn how to work the land, how to build a relationship with it, and how to build communities such as ours.

We were a group of peace activists from Israel and Palestine. We wanted to create a similar model in the Holy Land based on peace research. We went to different places in Israel and Palestine, and Israelis and Palestinians met between each other.

We met some difficulties along the way. When the Israelis and the Palestinians had to live together under one roof, the conflict influenced their relations tremendously, and it became difficult to detangle ourselves from it. On the other hand, we learnt a lot from this experience.

While I was working on all of these projects, my child was growing, and she became part of the community, so when we wanted to make a second experience in Palestine and Israel, my daughter asked, if the two of us could stay in Tamera. So we stayed, and that allowed me to develop the career of being an international speaker and being able to network.

I love Tamera, because the place has created a new model of living, where people's relationships are based on trust, transparency and mutual support. We always say that we don't know, what the solutions for world peace are, but we try to live a life that walks the talk, and we try to activate the peace theories in life.

The lifestyle in Tamera is based on sustainability in everything from food, water, energy to community. For example, today was my duty to work in our garden.

We have almost reached 100% sustainability, but what is even more unique about this place is the social life and the research carried out on the topic of reconciliation, for example reconciliation between men and women, which is a big issue especially in crisis areas, such as Israel and Palestine. These are very patriarchal societies.

I just came back from being in Palestine for three weeks, and I go there three to four times a year. When I am in Palestine I miss Tamera, and when I am in Tamera I miss Palestine. My culture is represented in Palestine through my heritage, culture, religion and language, while I have a tribe in Tamera. I am a lucky person, because I have two homes in two different places.

Nurse

I worked as a nurse for 15 years since the age of 18. Being a nurse wasn't something that I had wished for actually. I actually wanted to be an engineer, but my father thought that studying to be a nurse was better for a woman, and because I loved- and admired him so much I did it - although I didn't believe in it. I did enjoy it at times, and I guess it has done me good as well.

The time around the Second Intifada was what made me quit this profession. I really couldn't do it anymore.

At that time we would receive both the soldiers and the suicide bombers, and I had to treat them both. This took me to places that I could not deal with anymore. I perceived the soldiers and the suicide bombers as equal and as equal victims of the system here. I felt like we kept curing the wounds of people caused by this system. We just treated the symptoms. This wasn't sustainable nor right. In order to stop this, to really help, we have to go to the root of the problem, this conflict. I couldn't imagine continuing to be a nurse. I knew that those that I had helped would be thrown into this sick society again.

The Second Intifada was particularly brutal and extreme, but it's really a sick society that we live in, breaking families, tearing love apart, and breaking societies. It's because we don't live our truths - we don't live our lives in the right way.

I recall how around the end of the First Intifada, as a teenager, I had felt that this was it. We had made our revolution, we had achieved something, but the Second Intifada really ruined all of this for me. We really had done nothing.

If You Walk Out The Door

My ex-husband and I were in love. It was like a normal love-story, and we eventually got married. Five months into our marriage, we developed a conflict, and then he told me: "If you walk out the door, we are divorced." I thought he was kidding, but he meant it.

We were both stubborn and we did't have mature wise people around us to advise us in how to go forward. Nobody approached us asking us why we were having these troubles. Everybody is busy earning money to feed the system of exploitation. We are a society of slaves of a new order.

It became more difficult, and the gap between us became filled with enmity and hatred. So we eventually got divorced, which came as a surprise to me at the time. I was pregnant at the time, and I felt abandoned. I don't know how he felt about it, as I didn't hear from him after this.

Not Israeli

Until the age of 14-15 I had this big illusion about how I was equal to all other Israelis here. I just had a different culture, language and religion. My father also had a lot of Jewish friends, and I related to the.

Then began the First Intifada. This was a wake-up call for me. To see children throwing stones reminded those of us living within the Green Line of our unspoken history. It was a united effort among all Palestinians to change the situation. That is when I began understanding that I am not an Israeli. We are not equal, not the same.

By the age of 16 on "Land Day" on March 30th I was put in prison. I was arrested because I had put up a placard on our balcony saying "territories for peace" with a Palestinian flag and an Israeli flag. I wanted to express my thoughts, and this phrase was a phrase that had been said quite a lot of times by Yossi Beilin, although it was still a controversial thing to say at the time.

I recall how I had left it on the balcony. I went to help my mother with the cooking in the kitchen, forgetting about it. Two hours later, ten soldiers and police officers turned up at our house in jeeps and arrested me. It was a humiliating experience for me and my family.

I didn't understand the danger of what I had done. I had just written one phrase on a placard accompanied by the Palestinian flag and the Israeli flag. It didn't harm anybody, but I was accused of assisting terror associations, when I, at the time, didn't even know what the word "terrorism" meant.

I spent two thirds of a night in prison, and this was enough for me to understand that I wasn't living in a democratic state, and I wasn't considered an equal in this land.

My father and I were forced to pay a fine of 1000 shekels, which in 1987 was a huge amount, the equivalent of 10.000 shekels today. My father could pay it all in one payment, but they forced us to pay it bit by bit, so on the 10th of every month for ten months I drove with him to Afula and had to hand them 100 shekels, while restating that I wasn't assisting terrorism. It was humiliating every time.

Forgiveness

It has always been natural for me to spend time with Israelis, because I grew up with them. Back then I liked, how we were represented as "cousins." I find some similarity in Israeli culture, the healthy one, and I love the Hebrew language. I studied in Hebrew at the university.

I feel however that Israeli culture has bad roots. I am not speaking of a Jewish culture but societal Israel. In a lot of the cases that I have worked with Israelis, I have felt as if they insist on taking all decisions and then pretend that our work is a result of cooperation. On the other hand, I have worked with a lot of Israelis, who know how to cooperate, how to give space to each other. It's not really about their nationality, but the sickness of the society that they live in.

I forgive very easily, and I have forgiven Israelis for what happened to my family in 1948. Three quarters of my family died, and the rest were kicked out to Syria and Lebanon. Yet I do not forget anything, and in the process of making peace, stating justice and asking for forgiveness is very very important.

For those Palestinians, who have difficulties in collaborating with Israelis, I can understand them. I can't say, what it is like to have lost a loved one from your family in recent years, or how it must feel to have been affected by one's house demolished. I'm in a privileged place.

It's also not like this conflict has ended. It is continuing, and the atrocities of the occupation are continuing.

So what I demand from myself in terms of forgiveness I don't demand from others. However, I am with them in terms of not having forgotten.

Interview conducted on December 11, 2015 by Sarah Arnd Linder