HER STORY #76 - ilana

A Cat’s Point Of View

My name is Ilana Zeffren. I’m soon 47 years old, in October, but I feel 16.

I’m a lesbian, single right now. I live in Tel Aviv with my two cats.

I’m an illustrator, within comics. I illustrate children’s books, but most of my work includes texts of my own and not of others.

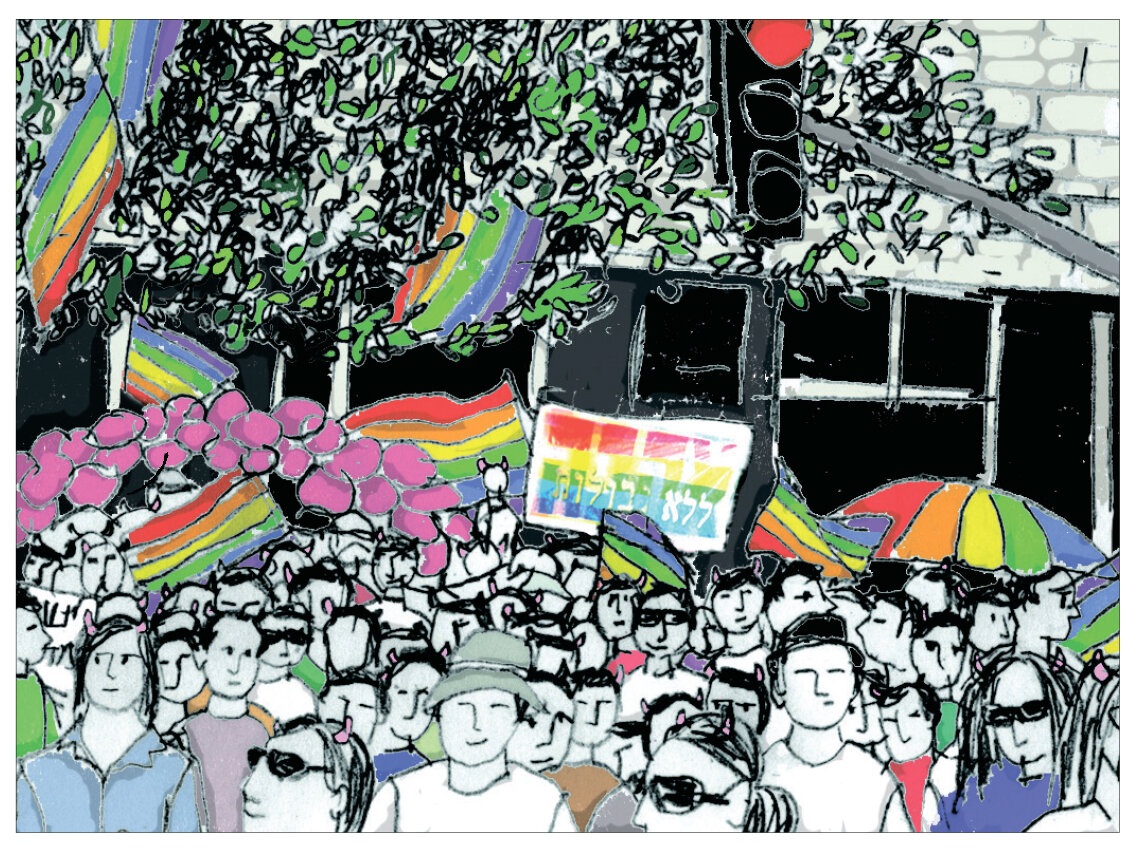

“caricature from Haair newspaper”

I also have a one-frame cartoon in Haaretz [Israeli newspaper]. I’ve had it for six years, on a weekly basis. The stars in the cartoon are my cats, and it usually deals with current affairs, such as reactions to something that happened during the week. It’s from a cat’s point of view.

Israeli Perspective

Sometimes it [cartoon] is just funny. I mostly try to be funny, although sometimes the cartoon can reflect something emotional. For example, if a singer died, the cartoon becomes a sort of ode [to the singer], but usually my cartoons are funny.

Many times, they [cartoons] also carry a leftist message, or one of peace, tolerance, acceptance of the other, human rights etc. That’s my cats’ take on it – and it’s there between the lines.

There is a lot of criticism of the government, but it’s also very Israeli. The cartoons deal with the holidays, the weather, and the big summer holidays. It’s like a combination of unimportant things in life [in Israel] and wars.

When I had a page in the newspaper, it was an autobiography, but which also dealt with current affairs. It was a lot more personal, but now what I do is less personal, and it always deals with things from a very Israeli perspective. There are many things that I do, which I wouldn’t be capable of translating, because they are very, very Israeli and deal with things happening here.

Pink Story

I studied graphic design, and illustration was part of it. I didn’t study cartoons at all. When I went to college, studies in cartoon specifically didn’t exist, but today they do. You can specialize in cartoon illustration.

When I finished my studies, I wanted to be an illustrator, but I mostly worked as a graphic designer, because I needed to make money, and so I would do some illustrations here and there, but I didn’t include any comics in my work. It wasn’t my goal at all.

Yet, then by coincidence I broke up with my girlfriend in 2003, and it was a dramatic break-up, very dramatic and like I was in a telenovela, and then I got the idea of telling about this break-up through a comic, because I saw the potential of this through storytelling.

It was sad and ridiculous at the same time.

From the graphic novel "Pink Story"

It got published in a LGBT-newspaper at the time called Ha-Zman haVarod [“The Pink Time”], and then I began to understand that it [cartoons] is a language that fits me, and at the same time I got more interested in the combination between illustration and text and to tell a story in a graphic way.

Then I was very lucky, because, based on that, I got an offer to publish a graphic novel. It was my first book – published in 2005 – called Sipur Varod [“Pink Story”]. It’s a combination of my personal story, including my childhood, and the story of the LGBT-community in Israel, from when it was illegal to be a homosexual according to the law, while, at the same time, being about my story, from when I was a kid to when I moved to Tel Aviv and met my first girlfriend.

So, the first thing that I did was a book, which is rare. Usually people in this field begin from smaller things, but because of the book I understood that the path of autobiography and current affairs interest me, and I began doing comics, which got published in Achbar Ha’Ir [magazine], until that newspaper closed.

Unlike my early comics that had to do with LGBT-issues and my identity, my comics In Achbar Ha’Ir dealt with a variety of subjects. It was more mainstream in a way, but in the background, there was always my lesbian relationship and lifestyle. And I presented it as a normal way of life.

Language

If you would have met me, when I finished my studies and told me that I would work in comics, I would have said: “No way,” but when I look back, it actually all makes sense, because when I was little I liked to write. I was the kind of girl, who wanted to become a writer, but then I’d throw my writing away eventually, and I began drawing. Then suddenly at a later age, the text and illustrations combined to become one thing, and I understood that that is the language that I connect to.

Then from there things happened, and I’ve done all sorts of things that I thought I wouldn’t do.

I teach a lot, mostly children. I conduct a lot of lectures, and if you’d once said that I would lecture, I wouldn’t have believed it.

I teach lectures through a National School Cultural Program, managed by the Ministry of Education. It’s a school program, mostly present in peripheral areas but not only. The schools can invite lectures conducted by writers, artists and within other fields.

In these lectures I tell the children about my work and my autobiography through comics. I also lecture for smaller children as well as adults.

Military Base

I was born in Rehovot. Until the end of first grade we lived in Rehovot, and then we moved to Ashkelon, so I grew up there, and then I got enlisted. The army base was in the South of Israel, close to the border with Egypt.

I served in the army’s intelligence, in Arabic, because my high school degree included a major in Arabic. I served in Unit 8200 [Israeli Intelligence Corps].

It wasn’t such an important position.

I mostly understood Arabic – more than speaking it, but I don’t remember most of my Arabic today.

I liked it [army service] a lot. It gave me a lot, socially, as it was the first time I lived outside of the home. I served on a closed military base, which meant that we would spend ten days on the base and then ten days at home, so most of my life was centered on the army base and not at home, and so you develop a routine in that place.

And I liked what I was doing. I even signed on to do three more months. It was to earn money, and the people were nice.

When I enlisted, the question of whether to enlist or not didn’t really exist, but if I had to enlist today, I would have reservations. Today every [high school] student might have reservations, but back then it was different. It wasn’t even a question. It was clear that one had to serve in the army, but at the end of the day it was a good experience – maybe a small waste of time.

Think about it: Two to two and a half years of your life I could have travelled, studied or done something else. Yet at the same time I don’t see it as a waste of time, because it formed me and I learnt things, and I also made a comic out of it.

Me Too

Soon a book called “Drawing Power” will be published – an anthology collecting “me too” stories. It’s an American comic anthology, made by all sorts of women artists, who get to illustrate cases of sexual harassment that happened to them, or worse than sexual harassment, and I did my story of sexual harassment, which happened to me in the army.

Back then I wasn’t aware of it at all. I didn’t think about it.

It’s sexual harassment on the level of commanders making sexist comments or getting too close to you or hugging you [when not appropriate]. It’s not something dramatic. It’s “light” harassment.” Of course it’s not legitimate, but back then it was like that. Today it’s not acceptable.

“From "Top Secret", "Drawing Power"“

[The “me too” anthology] reminded me of cases, where I had been harassed, and I began wondering, whether I should illustrate another thing that I experienced – a case of verbal harassment in the US, which was a little more serious – but I chose to illustrate my experience in the army, because it’s a personal experience, which completely mirrors the political. It’s very common for army commanders to harass [female] soldiers.

It’s not that I wasn’t aware of it [at the time]. I was aware that there was sexual harassment [in the army], but it didn’t bother me really. I ignored it. Today it really disgusts me. If I see something, it disgusts me, but it was part of the daily life in the army back then.

Tel Aviv

I’ve lived in Tel Aviv since the end of 1998. I’m a complete Tel Avivian. I deny any connection to Ashkelon. I really don’t like Ashkelon, because it’s a kind of periphery.

I didn’t move directly to Tel Aviv [from Ashkelon]. I moved to the North first, to Haifa, Nahariya, and then when I moved to Tel Aviv, I became to understand that Ashkelon isn’t open-minded.

I don’t know what it’s like today. I guess that today it’s better, but if I compare my generation, who grew up in Tel Aviv and myself and my generation, who grew up in Ashkelon, those in Tel Aviv were much more exposed to culture and the world. We [in Ashkelon] are a sort of village.

I think I sort of closed the gaps [by moving to- and living in Tel Aviv], but back if I’d grown up in Tel Aviv, I would have been a much more open-minded person, and from an earlier age.

Because I grew up in Ashkelon, I like Tel Aviv in a very extreme way. I don’t take Tel Aviv for grants.

I’ve never wanted to live elsewhere. I did want to travel for a couple of years and study elsewhere (a second degree perhaps). There were periods, when I considered this, and once I lived abroad with my ex-girlfriend for a couple of months, but still, Tel Aviv is the place.

People Here Really Like Cats

Because I express my opinions through my cats, I cover it in cats’ fur, and then it prevents all sorts of confrontations [with people].

Sometimes I tell myself that I’m naïve, because most of those who see my things, such as Haaretz readers, have the same political opinions as myself, including those who see my illustrations on Facebook. However, sometimes, at different events, religious people or people, who live in settlements, stop and read my work, and they laugh and smile. It’s obvious that they have different opinions, but it still makes them smile.

"Petting corner,” Haaretz weekend edition

There have also been cases of religious people coming up to me and saying: “Oh, I know this. It’s nice.” It creates a bridge, and that’s due to the combination of humor and cats. Humor alone is not always enough in caricatures, when they are obvious, but here it’s “lighter” and “softer.”

It’s partly because of my personality, but it has a lot to do with the fact that it’s through cats, and people here really like cats.

I see the variety of people, who see my work, ranging from children, who also like the cartoons but might not always understand them, to students who study gender, and who perceive my work from a feminist point of view, and then you have elderly people.

There are different kinds of people, who like the cartoons – some because of the cats, other because of the politics and others because of the arts.

Today I Want To Shout

In the last two or three years there has been a sort of environment based on how leftists are traitors and this whole dynamic of things becoming more right-wing, and this has made me want to express my leftist opinions even more. It seems even more important [to me] to let these things out because of their supposed “illegitimacy.”

I guess I’m not really succeeding in it, because I’m a careful person, but I kind of want to shout. Once I wanted to say: “Stop the occupation.” Today I want to shout: “Stop the occupation,” because everything is becoming more extreme.

I want people to be shocked. That’s how my cartoons have power: They are “light”, but they have a shock-value.

For example, sometime ago I published an illustration about the expelling of Philippine children, who grew up here. In the cartoon, Rafi (my deceased cat), stood with some other cats (in heaven), and one of the cats asks: “What is Israeli in your eyes?” All the cats give an answer to that, such as “cat ladies” and other things related to cats, and then, as the last one, Rafi answers: “A Philippine kitten that was born here.”

So, it [cartoons] touch people without bring crude. Instead of saying: “It’s not moral. How can one do this?” I give them this.

Home

As a girl politics didn’t interest me so much. I wasn’t involved in anything political, but my parents were, sometimes. They would go to different activities focused on dialogue between Jews and Arabs, so my home was kind of leftist and tolerant. I did grow up with this thing, but it didn’t really interest me as a girl. It developed, when I became an adult – when I began to read newspapers more.

At the time [when I was a girl] there were all sorts of initiatives, such as those where Jews would visit Arab villages [in Israel].

They [parents] were very much in favor of dialogue [between Jews and Arabs], so I was also supportive of that, and I remember that when I went to high school, my class went to Nazareth to visit Arab children, and we spent the day with them.

It felt natural to me. It wasn’t a problem.

Since then, I’ve been to many protests, but I haven’t been that active.

Palestinian Women

I’ve never been in touch with a Palestinian, I think.

The closest I got to this was when I took part in a project created by B'Tselem [non-profit organization whose stated goals are to document human rights violations in the Israeli-occupied territories]. They collected testimonies of Palestinian women.

There are many cases of women, who were born- and grew up in Gaza, and then they got married to a man in the West Bank, and they move to the West Bank, and then Israel makes it very difficult for them to visit their family in Gaza, or sometimes they have to wait years to be able to travel to a place, which is basically physically close to them, and when they are allowed to travel there, they have to travel through Jordan.

“From "Asmaa's story", B’Tselem”

I’m not sure if B’Tselem collected testimonies only by women from Gaza, who moved to the West Bank or vice versa as well.

Anyhow, each testimony was illustrated by an artist, and I illustrated the testimony of one woman, and all the testimonies were made into comics.

But I never spoke to that woman. I turned her testimony into a comic, but I don’t even know what she thought of it. I guess she has seen it, because B’Tselem are in touch with these women.

Ambulances

There was a period, when I lived in Tel Aviv, where there were many terrorist attacks. It was very scary, traumatic.

I remember suddenly hearing ambulances, and then we’d know that something happened, and until today, when I hear ambulances, I hope it’s not because of a terrorist attack.

Until today it reminds me of that, because it was a period, where every other day you’d hear an ambulance, and something like that had happened. It was scary.

Back then I wouldn’t go on buses because of the fear of attacks, but today I do, because today, knock on wood, you don’t have such attacks. You mostly have them in the Palestinian territories.

Apathy

Today the political situation here shocks me on two levels.

On one level, it shocks me because there is the occupation. They [Palestinians] don’t have a country of their own; they don’t have a life, and this is something that has been going on for years. On another level, there is apathy, denial. There is a sort of denial among Israelis. Nobody cares.

Once people were more aware of it: There is an occupation, and it needs to stop. You could argue about it.

Up until two or three years ago, people would still talk about it [occupation], but today people are sort of ignoring it.

Then when the occupation is mentioned, most Israelis only care about it from a security-point of view – that we are in danger, and what to do in terms of that.

From what I remember, the occupation was always mentioned from a security-point of view, but there was also an interest in solving it for the sake of the people living there.

Today that doesn’t matter. The right-wing doesn’t care. It’s only about Jews, Israel and the lack of our security.

People have gotten used to it [occupation]. You begin taking it for granted, something that once shocked you. People sit and live in this reality, and they don’t care.

Today it’s like: There are people in Gaza. What do we care? It’s a kind of apathy. It doesn’t scare me. It’s just not moral or humane in my opinion.

I’m still surrounded by leftists, and in Tel Aviv you don’t feel it, because Tel Aviv is a bubble, but then the situation becomes even more extreme, because once the gap between progressive Tel Aviv and the rest of the country was small. Today it seems like a much bigger gap, and I’m not optimistic about that.

I can also say that in some way I ignore the occupation. In my daily life I live in the here and now, and I will lie if I say that it affects me, and that I sit and think about it every day. It’s something that’s there, but it doesn’t affect my mood in my daily life. It’s something bigger. It’s an exhausting reality in the background.

We Should Have Solved It A Long Time Ago / Five Minutes

My perfect situation would be for there not to be countries – for everyone to be able to choose where to live. Land [for me] doesn’t have a significance. I’m for the human being, not for land, but of course there needs to be countries, because most people would want to have countries, so I would want for there to be a Palestinian state and to have peace, so that [Palestinian] people there could work here.

In 1993-94, during the Oslo talks, we had five minutes of a sort of peace, and I remember, for example, that Gidi Gov [Israeli singer, TV host, entertainer, and actor] visited people in Bethlehem.

There were five minutes of coexistence, which I really remember, because it was so beautiful, and I felt that things could blossom.

So, the ideal situation would be for there to be two neighboring countries, and we would be able to visit each other, and they [Palestinians] could come and work here and vice versa.

And, because of my perspective of not caring about land, then of course I don’t care about East Jerusalem. If that is what will solve it [conflict], then what is the problem with dividing Jerusalem? I don’t understand it.

Is it better for people to die for nonsense like this? It’s very stupid. It’s a stupid world – so much unnecessary suffering on the Palestinian side and so much death on both sides. There is no justification or excuse we can give for this. The situation is our fault, the occupation fault. We should have solved it a long time ago.

“From the comic book "All about Rafi"“

Interview conducted on August 27, 2019 by Sarah Arnd Linder