HER STORY #7 - Tamar

"Me with the Israeli flag"

Emergency Routine

Last summer I was staying with a friend in Tel Aviv, and I was there at the beginning of the war.

The first time the siren sounded in Tel Aviv, I didn’t even notice it. I wasn’t prepared for it at all, and I slept through it. The second time it sounded was in the morning, and I remember at first wondering what it was. When I understood, I began thinking, “Well, it will probably stop before I get a chance to get out, so why even bother?”

My girlfriend lived in this very old, pre-1948 building, and I thought to myself, “Will this building even hold?” She was abroad at the time, and I stood under the stairs with some of her neighbors, all young Israelis. While it was a very new experience for me, they had obviously done this before. However, the whole situation was still nerve-wrecking for everyone, and we began cracking jokes in the stairwell. It was one of those odd psychological reactions that I repeatedly experienced during that summer. But then again, everything about those encounters under the stairs was surreal. Standing in such an exposed situation: once in my pajamas (re: underwear), and another time with shampoo in my hair and nothing more than a towel.

During the war I moved to another apartment. I had to do it as quickly as possible because we expected the siren to sound at any time. With this came uncertainty, which made moving more than a light backpack very unsure. Ironically, the moment I had finished moving my belongings into the apartment the siren sounded.

In the new building, there were children, which made the experience even less pleasant. When the alarms sounded, their parents tried to calm them down. Of the two children who lived upstairs from us, the oldest was always the first one out, and the youngest one cried a lot, except when he was too tired to do so. So there wasn’t much kidding around.

Not As Bad As Gaza

I actually never felt that unsafe in Israel because of the Iron Dome. I know it was a false sense of security, but then again living in Tel Aviv wasn’t the same as living in Ashkelon, and especially not the same as living in Gaza. If I compared my experience to the experiences of those living in Ashkelon, I had plenty of time to get into safety – a whole minute to a minute and a half. Time becomes valuable, down to the second, and in Tel Aviv, we had “plenty” of time.

The whole situation really affected my subconscious. My entire life routine was dependent on the expectation of the next siren. I didn’t sleep well because I was always alert. I would always think twice about taking a shower, because perhaps a siren would sound at that exact time—which it did once, when I was forced to go out to the stairwell in only a towel.

It was super irritating. But at the same time I felt spoiled for feeling what I felt. I would have been much worse off if I had had to be in Gaza. In fact, every time I heard the sirens with the following explosions I felt very sorry for the Gazans, because I knew that their own actions would hurt them much worse. In venting my ample frustration, I would repeatedly think, or even say out loud, “How stupid are you for shooting missiles at us?! It’s like shooting yourselves in the foot!” However, it turned out to be much more extensive than a wound to the foot.

Not Released For Grandmother's Funeral

I had been in the army for a little under one year during the time after the Second Intifada. I had become very ill and was released early. There had been many language difficulties for me in the army because I barely spoke any Hebrew. I had lived in Israel at the age of three, and when I returned for my first visit back, I was drafted into the army. Needless to say, I was quite taken by surprise.

I recall a moment one evening, during the scarce free time when we were allowed to make and receive phone calls. On one such evening, my mother called me and said, “Grandma is dead!” and she just hung up. I then called my aunt, or vice versa – I don’t recall this so well – and she confirmed it.

When I first heard the news, I was in shock and couldn’t stop crying. Only the day after did I get the chance to speak to my officer. I told her what had happened, and some of the things that she told me were that not only would it be bad timing to go abroad for the funeral, but also the swearing-in ceremony would take place the following week, and also that she was “just my grandmother”, meaning not my immediate family. In addition, she asked whether or not my grandmother was Jewish. I don’t know what her intention with this was, but to me my grandmother meant everything – Jewish or Christian. According to my officer it wasn’t so easy to get permission to leave the country merely for one’s grandparents merely. That same weekend I was supposed to stay at the base to keep guard. Luckily my adoptive mother (I was a lone soldier) called the army base and firmly told them to at least let me return to the kibbutz so that they could take care of me. I went home to my adoptive family that weekend, but never to Denmark.

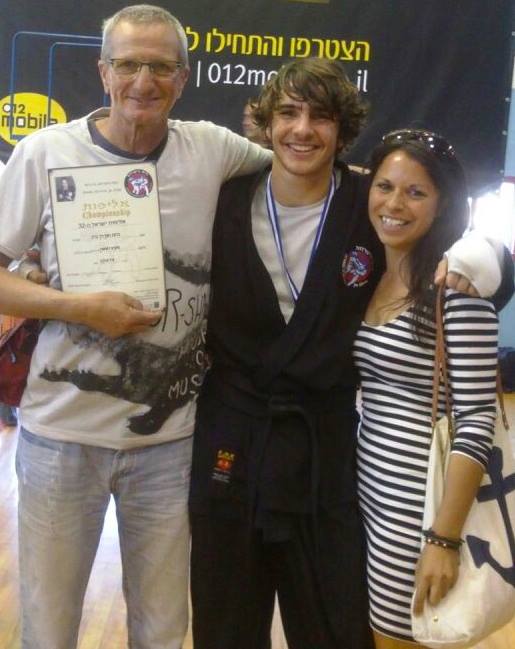

"Boaz and Jan (on the left), members of my adoptive family in Israel. Taken from when Boaz became Israeli champion in Jiu Jitsu within his weight class in 2014. We were so proud!

I have known him since he was four, when I became part of their family. Boaz just recently graduated from high school and will be going to the army soon but to his dismay only to become a jobnik [non-combatant soldier] due to back problems he recently discovered."

I was bitter at the army, but I also felt lucky for having such a marvelous adoptive family, that came as a result of my military service. Be that as it may, I hate chapels and hospitals, and although I didn’t get to see my grandmother, she lived on in my memory for a very long time.

To Be A Moral Soldier

Looking back on my time in the army, what frustrated me the most, and what I regret, is that I didn’t become a combat soldier due to all of the bureaucracy I encountered. This really made me feel contempt for the institution and for the time that I served. Even through my illness, I didn't experience any awareness or compassion towards what I was experiencing.

I had always felt that if I were to be recruited to the army it should be all the way. I went to several eye specialists in order to raise my profile, and successfully did so. I didn’t want to just sit behind a desk. Considering my Danish upbringing, I am convinced that I could have been a really good soldier. My moral compass is slightly more sophisticated. That’s not to imply that Israelis don’t have a moral compass—they do—but it is heavily influenced by having lived through so much conflict. The Israeli army is so much more than the wars in Gaza. I believe that it is important for all of us to set a good example: in the army and everywhere else in life. We shouldn’t preach morals, but rather share them, and it is for this same reason that I teach today.

When I was released from the army, I was asked if I wanted to join the reserves. I told them I would return to Denmark for good – I didn’t – and now I regret not serving in the reserves. If I was asked today to serve my last year, or if I was told that my service was needed, I would join, but along with me I would bring my moral compass.

"Two of my closest friends: Erik and Andreas. Celebrating Andreas' (red coat) birthday together in Sweden."

Interview conducted on June 11, 2015 by Sarah Arnd Linder