HER STORY #68 - mayan

Background

My name is Mayan. I’m soon 40 years old.

I’m a mother to two children, a son who is 13 years old and a daughter who is 11 years old.

I’m a teacher of young grades in the democratic school in the community.

And I’m divorced. I live with my partner, who also has a child, so sometimes the house has zero children, sometimes one, two or three children.

I grew up in a kibbutz, a community kibbutz, where we, as children, shared beds, and everything was shared. My family still lives there. I left it at the age of 16.

I didn’t like the kibbutz at all. The kibbutz framework was very, very difficult for me – to find myself, to get some kind of acceptance from the society, especially when I became a teenager, and I felt that I wasn’t seen in the kibbutz.

My parents really supported- and understood me and helped me find the way out, and then I would come back once in a while, but I never really got involved with it. It just became a geographical place.

Now I’ve lived four years in Tel Aviv, and we moved to Yafo [Jaffa] in April.

Kiryat Shalom / Yafo

Yafo is very different.

We lived in Kiryat Shalom [residential neighborhood of Tel Aviv]. Kiryat Shalom is a relatively very religious neighborhood, and we felt very much like outsiders there. It was before I moved in with my partner, so it was me and my children living there, and a woman living alone with her two children was a weird thing. Also, my children wore whatever they wanted to wear, without a kippah, and sometimes children would throw stones or tomatoes on them. Some would also stick their tongue out at them. That is part of the treatment they got by other children there.

In class at some point, my son was asked to talk about an example of when he had felt discriminated against, and he answered that he had experienced it in his neighborhood. That is when he had felt different, in terms of us being secular and everyone being religious.

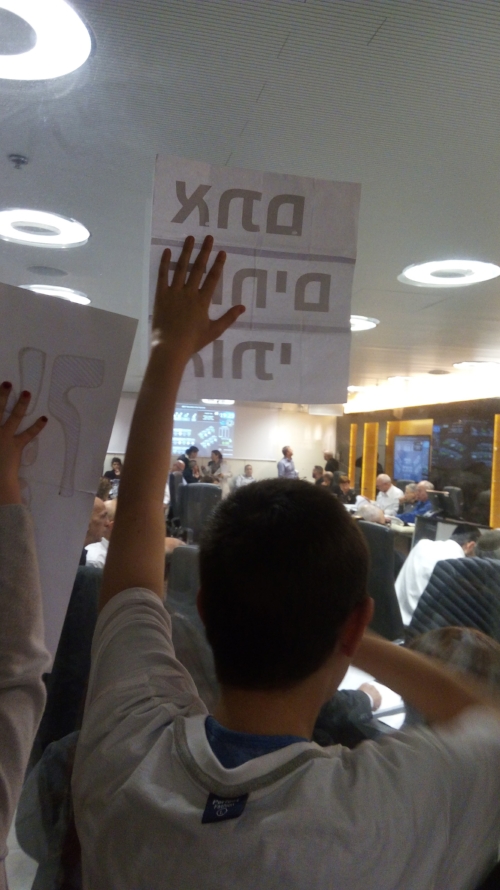

"My boy protesting against the city council decision not to give his school formal recognition."

When we moved here [to Jaffa], I was walking on Sderot Yerushalayim [Jerusalem Boulevard in Jaffa], and I asked my daughter, if she liked Yafo. She said: “Yes, I like it more than Kiryat Shalom,” so I asked her why. She said: “Because in Kiryat Shalom, there were all sorts of pamphlets about ‘real Jews,’ and here there aren’t.” And I think this is what it’s about.

The population is really more mixed [in Jaffa]. When we moved, which was a little bit before the Ramadan, my children fell in love with going and seeing all the lights [in the streets], and all the sweets that they sold, and they were really interested in knowing about the [non-Jewish] holidays, which they hadn’t heard about at all, such as the call for prayer from the muezzin.

That’s also what happened in the south of Tel Aviv around Christmas, mostly in Shapira [neighborhood in south Tel Aviv], where different kinds of populations live. Suddenly you begin understanding that there are more things apart from what you already know.

So that’s one thing that there is in Yafo, and I also think it helps a little bit in terms of keeping sane. When you hear Arabic in the streets, when you meet different people all the time – it helps not to get all this information [about different people] through the media only or through the racist utterances of people and to actually experience people here.

I don’t feel that people hate me when I walk in the streets, and I don’t hate anyone when I walk in the streets.

In Kiryat Shalom I felt foreignness. I felt that I was being judged, that people were staring. For example, my neighbors would look at me, if I wore a tank top or shorts. They didn’t say it out loud, but I saw the looks. I didn’t have much connection with my neighbors there, but the connection there wasn’t nice. I don’t have much connection with my neighbors here, but I feel that the acceptance of diversity is bigger.

The second reason why we moved here is connected to slow movement, which has to do with sustainability and the production and processed industry. For example, one of the things that is very comfortable here is that you don’t need a supermarket, as this area has the construction of what towns used to be. I don’t need to buy a lot in one go anymore, and I can buy things that aren’t from big companies. Here you have milk products that aren’t produced by big companies such as Tnuva and Tara. You have products from small dairies, usually from Arab villages.

And it makes it more comfortable to manage this kind of life.

Besides, my children’s school is very close to where we live. It’s a walking distance, or my children can also get there by bike, at least instead of a car.

Kibbutz

After my divorce I lived in a kibbutz. I went to live next to my mom in a kibbutz. I live there, but nothing in my life took place there. My children went to a school that most of the children from the kibbutz didn’t go to, and all of my work was here in Tel Aviv. Also, all of my relations, apart from the relations with my family, didn’t take place there [in the kibbutz].

I think that when I grew up in the kibbutz there was some form of expectation to go on a specific path, to be something specific, and I don’t think that I fit this, and I also didn’t know how to play the social game – to, as a girl, understand the social standings. I didn’t know how to suck up to the class’ queen, and I would do what I thought was right for me, and it didn’t always fit.

The same group of children grow up together from age zero for ever. It just doesn’t change. We were a group of 20 children, growing up with each other, from the age of zero. You don’t have another place. They are always together, and I couldn’t find myself there. I felt that in order to be part of these children, I had to do things that weren’t right for me, to think in a specific way and to do what everyone was doing.

I don’t think it was something conscious even. I think that I just didn’t understand that I had to do what everyone was doing. I just had my own perspectives of things, and I didn’t fit the whole group.

Afterwards when I spoke with people who grew up there, I knew there were others who felt like this, that didn’t fit in, but they didn’t do anything.

If I look at it today, I’m very happy about the ways in which these things happened. I see people that I grew up with, where everything in their lives seem to have stayed mediocre in terms of their ambitions and their way of thinking, which also is very bourgeois.

I raise my children very differently than them as well without the big focus on capitalism and consumerism, which is funny, because we are talking about people who grew up on a kibbutz, but it [kibbutzim] hasn’t been like that for a long time. So I’m happy that somehow my stubbornness opened the world for me in some way and it made me deal with all sorts of things.

Also, my father was a doctor, and when I was in sixth grade, he took a sabbatical year next to San Francisco and we joined him. We stayed there for a year, and for children who only knew life on a kibbutz, to suddenly be in another country and to speak another language and to know another culture, I think this also contributed to this – to my horizons being wider than what they were in a kibbutz. And it was difficult to narrow them down, when I came back.

Roots

I think that there was something in my family that contributed to making me the way I am.

First of all, in the kibbutz that I grew up in most of the people were either the founders of the kibbutz, children of those or the grandchildren of those, or they were the children of South American families, who had moved there for ideological reasons.

My mother grew up on a kibbutz but in another kibbutz, and then she met my father. He lived in Tel Aviv, and they lived in Tel Aviv together, and at some point she felt that she couldn’t live in Tel Aviv. To this date she doesn’t like being in cities; she needs space, and so they looked for a place to move to. The kibbutz that they eventually moved to was looking for a doctor, and so they moved because of that. They stayed there because of the children and also because of my mother.

So we didn’t have some sort of roots in the kibbutz. My parents were some sort of outsiders. There are also others like this in the kibbutz, but my mother said that even my caretakers and teachers were children of the kibbutz’ founders.

At the same time I also didn’t have grandparents in the kibbutz unlike many of the children whose grandparents were some of the kibbutz’ founders, the elders. There were some kind of roots [for them], and I didn’t have those. I had those in other places.

Ideology

My mother is a person who is very easy to like, and she is a much liked person.

On the other hand, my father wouldn’t compromise on saying what he thought was right, also if it meant getting into arguments with people. Many times his opinion didn’t fit other people. And I think that people were a little bit scared of him as well. He was just a person, who always said what he thought, and he also acted on what he was talking about. He was very ideologist, and he said it wasn’t enough to talk. One also has to act, and he acted within the ideals that he had.

He was a doctor at a public hospital, when he could make a lot more money in private medicine, but he didn’t believe in private medicine. He believed in public medicine. He believed in talking to the patients, seeing people. He was a doctor, and he said that there are very few doctors that really are doctors like pediatricians and family doctors. All the rest are plumbers taking care of the pipe, the skeleton of the building. They are people who deal with the system and not the person him/herself, and a real doctor needs to look at the person as a human being, so he always followed his truth, no matter what, also when he got enemies on the way, and he was very fearless of the results of his actions.

He was one of the founders of Physicians for Human Rights. Today it’s located in Yafo, but once it was located next to Tel Aviv Central Bus Station.

He would go to the [Palestinian] territories once a month or every second week. There was a hospital and a school that he worked at, where he would treat people, and sometimes he was stopped because of that and was investigated by the Israeli police at checkpoints. In addition to this he would get all sorts of reactions from all kinds of people, as he was “helping the enemy.”

At first he traveled to the territories to treat people there, but afterwards he also treated immigrant workers [in Tel Aviv].

I think I was about 16 years old, when Physicians for Human Rights was founded.

Kanafeh

We were in the U.S. in 1988-89, the year the First Intifada started.

I didn’t have a sort of political awareness back then, but I remember that my parents would get letters from Israel, and they got very worried, really worried, and there were these talks with the word “Intifada” at home.

I remember them really following the news in Israel and being worried about the situation, and at the same time they followed the work of all kinds of initiatives for peace, made up of Palestinian and Israeli students – all these kinds of initiatives that were trying to bring closeness [among Palestinians and Israelis].

My mother is a widow of someone who died in the Six Day War [in 1967]. Then she met my father and got married. Every year we would go to Jerusalem to the Ammunition Hill [in Jerusalem], and after that my father really liked to take us to the Muslim Quarter in the Old City to eat kanafeh [Middle Eastern cheese pastry]. And I remember that when we came back from the US we didn’t get kanafeh, because it was dangerous, but I remember not understanding why it was dangerous.

My father believed that there needed to be peace and dialogue, and he looked for ways to be able to contribute to that and with the cooperation of others.

In contradiction to Doctors without Borders, who would always go out to places, he would always say that we must work within Israel and try to fix things here.

So my parents really contributed to making me follow the things that I believed in, and I also grew up with a humanistic education: A human being is a human being. It doesn’t matter what religion or nationality he/she has. A human being is first of all a human being.

I really don’t know how my parents got to this place, but I think that it was a combination of my father’s ideology with the very sensitive side of my mother. My mother has something that is really not violent or authoritative, and I see it every time she speaks to people. She tries to make people feel at ease, so, in opposition to how my father said what he thought all the time, she would think: Okay, this person is different than me, and I will respect that.

Politics

For years I tried to avoid politics. It’s also one of the things that drew me to the project [Political is Personal]. I don’t see myself as someone who understands politics. I understood this way of thinking of mine this year really strongly – in terms of the fact that I just don’t know how to act in a political way.

I participated in some sort of demonstration for the school vis-à-vis the municipality [of Tel Aviv]. I was there with a friend, and he is very active in all kinds of demonstration for peace, for refugees, and Haaretz [Israeli newspaper] really likes to take photographs of him.

I saw his behavior in the demonstrations and he knows what needs to be done. He knows how to place himself, how to hold the signs, how to convey his political agenda and for it to have a presence. At the end of the demonstration, Huldai [Ron Huldai, mayor of Tel Aviv] got out of his meeting that he had [in the school], and he [interviewee’s friend] confronted him, and he was considerate, articulate, and Huldai was talking bullshit. I broke down seeing this stupidity and feeling powerless, and I saw him [interviewee’s friend] and he continued talking and he stood there. He was angry, but he was very serene in a place where I would break down. I was on the verge of crying.

And this whole year in the school, where a lot of the municipality’s politics has entered the school, I noticed that I give too much credit to people for understanding politics. I don’t take into consideration that perhaps people lie, that perhaps they have some form of interest, which isn’t in favor of the school but for their benefit, and if I give them my trust, it will hurt me.

And I really feel that I have some form of really naïve part of me that believes in good, and in the capacity of people to think logically, which doesn’t go together with politics here in Israel.

I have a friend who once said that Bibi [Benjamin Netanyahu] is a great politician, because he knows how to manipulate. The person who said this also added that the meaning of a politician is not that, but we connect the word “politician” with something corrupted as a result of the behaviors of the most recent politicians. That’s the connection we make now, but there is a gap, and I have a difficulty with this gap, between what you as a person believe in and what you say in order to please the society, for them to vote for you, because if they don’t vote for you, how will you influence?

Somewhere there I’m getting lost. Something is not logical in this whole thing that has to do with politicians. I feel like it’s a sort of game, about saying what people want to hear, and at the end I will do what I want to do.

And there is not really anyone to trust to change that.

Elections

During the elections I broke. It all became clear for me: For 20 years we have lived in this shit. People see how our government behaves. They see which decisions are taken, and how none of it is in our favor – for the benefit of the citizens. Let’s forget about the left-wing or right-wing, but just in terms of benefiting the citizens.

People are not capable of lifting their heads above the water and to finish the month in a respectful way, and I was sure that there would be a change, and when there wasn’t a change, it broke me. I lost my belief in the fact that there can be good here.

I understood that I had to try and find the exit out of here. I have to understand how to make sure I’m safe and my children are safe, because soon the day will come, where we will be persecuted – people affiliated with the left-wing.

Aggressiveness

I’m not knowledgeable in terms of what happens here – who this minister is, and who this minister is, and what the agendas are. I have some sort of a naiveté about there needing to be compassion in the world, and how there needs to be acceptance of people and the need to respect them, and when I look at the people who behave in a violent way, then I also have a sort of compassion for them. I will think: Wow, these people are so ignorant, they must feel so weak and so hurt.

I believe that people who behave in an aggressive way are people who feel threatened. If we look at animals: Animals attack, when they are threatened.

It has nothing to do with being affiliated with the right or the left or about Arabs and Jews. I also see how the only thing that interests people is money, and for them everything is about having things and about materialism, and as long as money, power and control will be at the center, I don’t think there can be peace in the world.

And on the other side, if we put people in the same bowl, including the leftists, the feminists (there are different struggles being fought and it’s very easy to see that there is one side here and another side there), but I also see that there are people supposedly on “my side,” who think like me, and also there you find a lot of militancy. People on “my side” also react aggressively towards the other side. At the end there is judgment. There is the “right” and what is “not right” on both sides.

There is a lot of feelings of weakness, and the source of that is that people feel the need to prove something to themselves, as a form of revenge. For example, you have feminists who hate all the men. They think as such: I’ve been treated badly, so I need to give back. That’s also part of the inability of being in the moment here and now, and this is also connected to how we always think about the past, and if we continue like this, where will it end?

Religion

For me it’s very difficult to live in the middle of this situation.

After having served in the army I lived in the U.S. again for three years, and there I saw myself as completely Israeli, Jewish and I thought to myself: I’m here for a little bit and then I come back to Israel. It’s my home and my place.

I don’t feel like that anymore, not only because I, myself, have changed, but because this country has changed.

Just by looking at religion, there is religious coercion, an expression that I know from my childhood, but now it’s really present. It really exists.

If I look at how things were when I was a child, many small things have changed. Today in the news they will mention when the Shabbat starts, and when it ends, and the week’s Parashat [Weekly story from the Bible] is recited. This didn’t exist in the news before at all.

Now on Tisha B'Av [annual fast day in Judaism] there are arguments about whether to let shops be open or not. Before shops were open, and it was normal. In this specific place where we live it was never forbidden to sell chametz [leaven, or food mixed with leaven] during Passover, even when the Temple Mount existed. It was only recently it became forbidden.

There is also something in the lack of feeling secure within our Judaism and what Judaism is. It all really pushed me out of Judaism, because I can’t see myself as part of this thing, this Judaism, because Judaism has become narrower and has turned into a very specific definition, where women don’t have a place, and everyone who thinks a little bit differently doesn’t have their place either.

Typography of Terror

In December I was in Berlin, and there I went to a museum called Typography of Terror. I didn’t mean to go to the museum.

The name of the museum confused me, and I thought I would go to a museum connected to the Middle East, the history of the East and the West, and I found myself in a museum describing the behavior of certain bodies creating terror from the years 1933 until the end of the Second World War in Germany – in terms of the SS etc..

The museum is mostly made up of images and documentaries, and it’s set up so that you go on a specific path. It begins in 1933 with the democratic elections, and it ends in a point that we all know about. You follow the path slowly, and you see the development.

This thing was so difficult for me, not in terms of how the Jewish people and what happened to them. It was exactly about what is happening here, and during the visit I said to myself: This already happened here, and this already happened here, and then we got to the point [in the museum], where people, who were different, were taken to concentration camps, and then you say to yourself: Okay, that’s where it’s going, and suddenly the picture became very clear, because we are there. The period between what is happening here now to when they will hang me ad probably you [interviewer] on Sderot Rothshild is not far away.

The day they will force me to put certain clothes on, like a chemise with a skirt is also not far away. It’s soon there.

Until my children will turn 18, I’m connected to this place because of the divorce, although during one of the conversations I had with their father I told him: “Listen, the day they will force my girl to wear certain clothes, that’s the day where I will leave, no matter what. I will take them and will run away from here.” The idea is not to stay here.

I don’t think that we [leftists] have a chance here. I see how much ignorance and being silent is blessed. To be an educated person is not something that is good.

During the last elections was when I began understanding this.

Ants

I have a funny story.

In the evening of the elections, I was invited over to friends to see the polls. They lived in a neighborhood next to us.

Before going I sat with the children. They saw some of the news. It interested them a lot, and they were eating in front of the TV in the living room, and I told them: “Take a plate, but be careful of not making any crumbs, because then the ants will come.” Then I put them to bed and I went to my friends to see the polls.

That evening there was some sort of result, but there was a gap showing a chance [for the eft]. I then woke up in the morning, and I turned on the TV and saw the results, and I stood in the living room and shouted: “No! No!”

My daughter came running from her bed and said: “What happened? Are there ants?” And I answered: “Yes, there are ants!”

Comments

During the same summer after the elections I went for one week to Denmark, and when I came back Shira Banki was killed during the Pride Parade [in Jerusalem], and the same week the house of the [Palestinian] Dawabsheh family was put on fire.

The two incidents were so close to each other, and the incidents hurt a specific population and was related to these specific populations.

My son took the story of Shira Banki in a very difficult way. He couldn’t understand how it’s possible to do such a thing – to kill someone, because he/she is homosexual, and they grow up in a democratic school, so they grow up in a bubble.

They worked on this campaign in one of his lessons calling for announcements to be in Arabic as well on public transportation following announcements made in Hebrew. The reactions they got from people were very harsh. They read them together with the teacher.

It was on the internet, as they had published it [the campaign] on Facebook, so they read the comments together with the teacher. They also made an additional video about the comments, but you could see the ignorance in the comments, such as “Arabic is not an official language in Israel.” Also, one of the things that people wrote was: “If you want for them to have Arabic announcements, then go to Syria. They will be happy to take you in there” and “let’s see if you can survive in an Arab country.”

My son told me: “You know, they wrote something very vulgar.” His teacher is homosexual, and he said: “They wrote that they hope that an Arab will fuck his [the teacher’s] wife,” and then he looked at me and began smiling: “But he doesn’t have a wife!” He was happy.

That was that summer. In the following month of March [2016] I suddenly woke up with the feeling that I had to take my children out of Israel during the summer for as long as possible. Because I’m a teacher I have a month holidays in the summer, so I can do it, and I had to find a way to get them out of here – there is something in this nightmare in Israel that does a lot of bad. With this constant struggle, I had to give them freedom from that.

It came like that. I woke up and said: “I have to; I have to save them.” And we went for a month to Holland. This year we went for one month to Sweden, while volunteering in organic fields.

For Granted

I did good hasbara [refers to public relations efforts to disseminate positive information abroad about Israel and its actions] work. I told the Swedes that really liked Israel about Israel, and now they love it a little bit less.

But there are really many things that we take for granted, and then we understand them, when we go out [of Israel].

For example, there are certain places here where there is no choice in terms of whether you want to go the religious way or not. You don’t have a choice. If you want to get married, you can’t choose it. It has to be a religious ceremony.

They [Swedes] asked me why my partner and I don’t get married, and I found myself trying to explain to people that there are places in Israel, where you don’t have a choice in being religious or not. You have to go the religious way, because that is what is in power here.

McDonalds

I think that what makes me afraid the most is religion, because it has something completely blinding. And the perception of many Israelis is this: Of course we have to do like this, because it’s religion. Placing question marks are not even okay.

For example: The daughter-in-law of my ex-mother in-law, the grandmother of my children, she keeps kosher. Then there is me, who is anti-globalization, vegetarian, anti-industrial food and trying to protect the environment as much as possible. She [mother-in-law] takes my children to McDonalds. For me, McDonalds is one of the symbols of all the bad things in the world, in terms of the pollution, the processed- and industrial food.

She doesn’t take the children of my sister-in-law to McDonalds, because it’s not kosher, and she won’t give them food that isn’t kosher, because she [sister-in-law] keeps kosher, but at some point I confronted her. I told her: “Why do you respect that [eating kosher] and this you don’t respect? “Because it’s the tradition, and of course you have to respect it,” she said.

She follows a tradition without even questioning it, because it’s written down that it’s forbidden to eat the goat in his mother’s milk, and it was translated into something loosely different, and people follow this ideology as if it is normal. And I chose my ideology from thoroughly weighing it, for the good of the Earth, so that you respect and this not?

And this is an example that happened within the family, but people will tell you that it’s horrible, if you eat a piece of bread in a public space during Passover, because it’s a lack of respect, but you think people will care about eating in the streets here during Ramadan, when people fast? Here you also have to respect. Or do you think they care about doing a barbecue in a public space? To place dead animals on the grill – animals that were raised within an industry that pollutes the earth the most?

Abortions

So the religion is what fears me the most, because people don’t ask questions about it. It’s taken for granted. People don’t question here in Israel.

You know that abortions for married couples is forbidden? The laws that cover abortion are Halakhic laws. Technically the council that approves abortions or not will allow abortions if there is a risk of danger to the fetus or to the mother, or if it’s not a result of marriage. Most women who do abortions are not married, so they don’t know yet, but if you are a married woman and you become pregnant and you don’t want the children, you won’t go to the council, because they won’t allow it.

The laws are Halakhic laws. Nobody knows it. You can do it privately, but you will need to pay money.

Even if the two [husband and wife] want, they can’t. Married couples who want an abortion will need to say that the baby was conceived outside of the marriage or they need to show that there is a problem or a risk.

Save Her From This Place

I need a passport [to leave Israel]. I don’t have one. I really need to find the way to do it.

There are [European] roots, but there is some form of law in Poland that says that if the Polish citizen served in the army in 1951 then he can’t get the Polish citizenship. My grandfather didn’t serve in the army but he got a personal number in 1950, so for them that’s the equivalent of serving in a foreign army. If it would have been a month after that it would have been okay.

When I got back from Denmark I met a good friend, who doesn’t live in Israel. We sat and talked, and after that I told her: “After this trip I don’t understand how someone who can just stand up and leave doesn’t do it. You can! You have a German citizenship. Get up, take your daughter and save her from this place.” That was really the way I said it, and she didn’t react too much, but she left some months after, and she couldn’t tell me about it, because it was in process, but eventually she told me that they were leaving.

With all the sadness of losing a friend and my daughter’s friend, I told her: “It’s the right thing to do. Good for you. You are giving your daughter an opportunity.”

If I leave - when I leave - I will miss things, but my longing are to things that don’t exist. It’s not here. It doesn’t exist. I can live here and miss home, because it doesn’t exist anymore. It’s not here.

The Gap

Apart from that, when I got out of the museum [“Topography of Terror” in Berlin], I understood the price that we pay. Forget about the economic price and the price of living in a country that is in a constant struggle for its existence. It’s about the price of living in a place, where all of what you are – morally, ethically, etc. – doesn’t have a place. I live here daily among things that I don’t believe in.

It reminds me of the kibbutz and of getting out of the kibbutz. It’s very similar. I always found myself seeing things in Israel and thinking: No, the complete opposite needs to be done. Not this. And everything that I believe in and all the values that I live by, all of my morals and all of my ideology – all of those things contradict what happens here, but I need to live with this in my daily life. All these things that I don’t believe in are forced upon me, and the gap between my perspectives and between that is difficult.

My ideology is not counted here. It doesn’t have a space here. There is no space for my morals and my ideals.

Municipality

The school that I work in is a bubble within Israeli society. There I find a lot of space, and therefore I can survive in the school, and I can raise my children there.

The school is presently facing an existential struggle. The Tel Aviv Municipality doesn’t want it, and perhaps soon also Bennett [Naftali Bennett, Minister of Education] won’t want us, and the Ministry of Education will throw us out. This school won’t be able to survive many years.

The mayor basically tells us: “You are private. I’m not ready to support a private school,” and we tell him: “We want to be a recognized school, where everyone who wants to go there can come and learn there, but we won’t give up on certain principles in our education,” and that’s how this dance continues with the mayor.

We had representatives from the bilingual schools meet with us at some point. They are currently working with the financial assistance of the municipality. They tried to open a school, and back then the municipality told them: “We will let you work with a dwindling school together, and we will let you work within your values that you wish to bring forward.” Six months later, they [bilingual school] understood that the municipality would not really let them work with their values and the education that they wanted, that the municipality didn’t respect the Muslim holidays and all other requests weren’t applied. And so they [bilingual school] came to us to see if there was a possibility to do a collaboration and to work together somewhere.

The municipality has also come to us and has offered us to work with a dwindling school, to give up on our high school and kindergarten, to give up on our team and promised that the school would be working within a “democratic spirit.” There are a lot of schools here working within this “democratic spirit,” but it isn’t democratic though.

The mayor’s claim basically is that we are a private, elitist school – in other words, saying that all of our children are rich.

There are 41 organizations in Israel related to education. 39 of them got a building provided by the municipality of Tel Aviv, even when a lot of their students are not from Tel Aviv but from outside of Tel Aviv. What all of these 39 institutions have in common is that they are religious. The last two are us and the anthroposophist school.

We are on the edge all the time. We will have to build from the beginning, if we close the school. When this option came up this year, we were thinking about having to leave and having to call ourselves something else.

Just to make this clear: The school was founded 12 years ago. It began with having 30 children, and teachers and parents were working together. Today, 12 years later, we have 400 children, and there is a very big demand. So it’s not like there is a risk at the school of no one wanting to attend it, and the bigger the demand is, the more we understand how bad it is outside.

Violent Organization

Apart from trying to find the way out [of Israel], I also have the thought of how the older my children get, the more present the story of the army is.

My father is an army guy, and I feel that in a hidden way – from his side – there is some kind of discussion in the family of supporting the idea of the army, against me, as I’m on the other side, always brainwashing them not to go to the army. Then I’m told that you don’t need to fight, and I say: “The army is an organization whose goal is violence, even if it’s defense or whatever. It doesn’t matter. Army in its definition is a violent organization. Do you want to be part of a violent organization?”

I find it scary, not so much because something could happen to them. They can go outside and cross the road and die. That’s not what is scary. What is scary is finding yourself in front of someone else in a violent situation, and needing to act against him/her in a violent way. For it to work out within yourself, you can do one of two things. One is to get out of the situation not hurt like a lot of Israelis do and the second, which is scarier, is to dehumanize the human being in front of you in order to be capable of shooting him.

It’s to close some part in you that is filled with feelings and then to become someone whom it becomes very easy to say things like, such as “death to all Arabs and to all leftists” that are hated in Israel, because we are not human beings. Something is closed there then, and there is no compassion.

That they [soldiers in the army] do what they are being told is clear. I see it with my son, Ori. I see how easy it is to brainwash him, and how it’s done there on the other side.

Brainwash

When we lived in Kiryat Shalom and we got out of the house, our car would frequently be covered with flyers, where it was written to stop the infiltrators and not to rent them houses, as they would pee in the stairwell and they would give us diseases etc. My son read it, and I asked him: “What do you think about this?” And he said: “Yes, it should be forbidden [to rent houses to infiltrators].” And I asked him: “Do you know what infiltrators are?” And he said: “People who are getting into the country in an illegal way.” And I told him: “Infiltrators are people who are refugees. Think about the refugees. You know their stories. So do you still think it’s okay?” Then he said: “No, it’s not okay.”

We had a similar discussion about what a terror organization is, and he said: “It’s very important for the Israeli army to fight the terror,” and I gave him the example of the Warsaw ghetto uprising and asked him: “Were those who fought in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising terrorists?” He responded: “No, they were freedom fighters,” so I told him: “One side calls them terrorists, and another side calls them freedom fighters. It’s the same thing. IDF fights citizens in organizations that are not an army, so we call it terror, but they see themselves as freedom fighters.”

And it’s so easy to brainwash them. It’s not only my son, who soon will be 13 years old, who is being brainwashed. It’s all the citizens in the country who are brainwashed. They are scared like hell by the murderous terrorist organizations.

Now I’m not saying that there is no terror. There is terror, but the terror also exists on the other side. We are not innocent.

All The…

In Sweden I tried to categorize the things that I think are those that enforce this situation and makes it continue, and I tried to understand what those things are. One of the things that I think are the cause for this are generalizations.

Every time that someone says “all the…” such as “all the Arabs…,” “all the religious…,” “all the seculars…,” “all the leftists…,” “all the rightists…,” “all the homosexuals…,” all the women…,” “all the men…,” “all the….” The moment you say “all the…,” there is no more a person. Then I am no more Mayan. I can be a woman. I can be a leftist. I can be Ashkenazi. I can be all the things that have stereotypes, but nobody sees me anymore.

I think it’s a human characteristic in the whole world. It also gives a lot more order, and it’s a lot easier. You feel a lot of comfort in a place, when you are part of something, but this “all” cancels the place of one. The moment I say “all the Arabs are killers,” I’m putting my neighbor in the same category as the Hamas fighter, but they are two different people, and the moment I say this I stop seeing them as human beings. It then becomes easy to kill them, and it’s easy to say “death to Arabs,” when “all the Arabs are killers.”

I remember when the refugees were referred to as “the cancer in our society.”

My mother used to volunteer at Physicians for Human Rights, after my father passed away. She was a therapist. She wanted to continue my father’s work, so she treated people who for six months had been sitting, in a cramped position, handcuffed in Sinai waiting for their families to pay for their release.

Real Danger

The time of Operation “Protective Edge” [reference to Israel-Gaza War in 2014] was the first time that my children experienced a war in some way. We had just moved to Tel Aviv, and on the first night in our new apartment in Tel Aviv, there was a siren. I was so occupied with the move that it took me a moment to realize what it was about. My daughter said: “What is this noise?” Then I understood that it was a siren and I said: “Let’s go out to the stairwell.” I hadn’t prepared them for it, so within that moment [of going to the stairwell] I had to tell them what it was about and how missiles were being fired at us.

It continued but they understood that they were not in a real danger, although it scared them a lot.

During the same summer we went on a holiday to the North [of Israel], and we slept in the cheapest hostel that we could find, where the rooms that were “apartment-protected spaces,” meaning if there was a siren we wouldn’t have to go out to the stairwell. When we came to the place, they were excited about it being apartment-protected spaces, and they would play with their Playmobile and pretend that there was a siren, and now everyone would have to find shelter.

For a whole year afterwards, they would react to every ambulance that passed, and the apartment in Kiryat Shalom was located next to a road where many ambulances would pass. Every time an ambulance passed, they would stand up and say: “Oh, it’s only an ambulance.”

Now these are children who weren’t really in danger. All they experienced were sirens and seeing the Iron Dome blowing up the missiles, which they could see form the window of my daughter’s room. At some point we also stopped going into the stairwell, because we understood that it’s not really dangerous.

That’s all they experienced, and they got scarred from this, so think about what a child in Gaza experiences or in the Gaza envelope [refers to the region of Israel surrounding the Gaza Strip] experiences, if he/she survives even…

Interview conducted on September 18, 2017 by Sarah Arnd Linder