HER STORY #64 - ruth

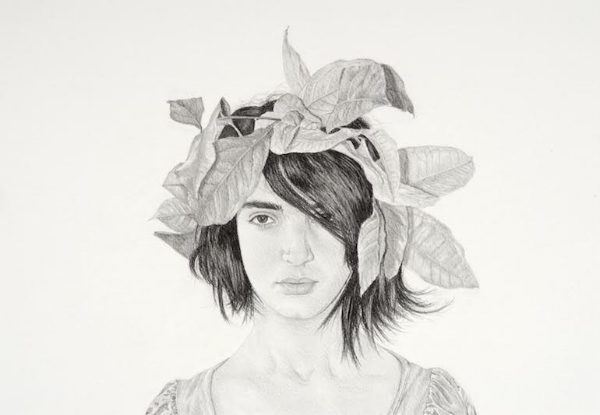

Samah Shaidi,Portrait with Lemon Leaves, 2014, pencil on paper, 40/30 cm

Thesis

I’m Ruth. I am 37 years old.

Until two weeks ago I worked at Umm El Fahem Gallery [Israeli-Arab art gallery located in Umm El Fahem]. I worked there as a project manager for four years, and I stopped on good terms, because I am now focusing on writing my Masters’ thesis, and I realized that I just can’t hold both things at the same time. My thesis has developed from my work, so I feel like it’s a good way to continue what I was doing there but in an academic way.

I left [the gallery] because it’s a very demanding work even though I was working part-time. I felt that I’m not in an age and position where I can work while being a full-time student. I have to juggle a lot of things since I also have two children, so it became very hard to really focus on writing and researching, and I felt that I want to give the research the opportunity to do really well so I decided to take six months to a year to focus on that.

Umm el Fahem, winter view.

Realistic Art

I’m focusing on three women, painters who all are Palestinian Israelis. They are all between the age of 30 to 40, and recently emerged within the art field and won prizes and have done exhibitions in museums and catalogues. Also, their work is being bought for collections and three of them are using a realistic style in their work.

Realism in art is a broad topic, which I will not go into details right now, but I am looking at the realistic style that these painters are using, and I claim that it serves them in different ways to be acknowledged as women artists in their own society and at the same time forming critical view on gender issues in that society within the paintings. The realistic style tries to mimic reality. It’s not abstract. It’s also not less expressive, but it really tries to depict reality in different and meticulous ways. It was the style of painting that until the mid-1800s, until the arts allowed itself to slowly drift apart from depicting reality.

Disconnection

Because of what happened since 1948 within Israel, Palestinians (and I’m not talking about Palestinians outside of Israel – that’s crucial) were disconnected historically and culturally from the Arab region that existed here before, and then for almost twenty years a lot of them were under army rule. When that was over, the main struggle was to survive. Culture and art were left behind.

4th graders meeting at the Umm el Fahem Gallery. Project Shared Space, 2016

Until 1967, there was almost no exchange of styles or traditions between [Palestinians] outside of Israel and the Palestinians within Israel. They [Palestinians in Israel] started being culturally active later on as a society, so they have a big gap in terms of the development of art history in comparison to Palestinians in Ramallah even.

Of course when I say art history I’m referring to Western art history. Of course it’s getting much more complicated, if you start asking what art history is.

There were 11cities in pre 1948 Palestine, most of them destroyed more or less within a few days, so when you completely erase urban life, then whoever could run away, and those who didn’t run away had to move out to the villages. By losing urbanism and middle- and higher classes, the Palestinian society after 1948, lost what urbanism brings with it – modernity, secularity, progress, and women rights. In a very short time, it was left as an agrarian society with no urban history.

Patriarchy / Subtle

Of course women have a harder time to do what they want. They are still living much more under a patriarchal society, where they have to answer to what their fathers want and what their parents want, and they are usually directed towards marriage, and like in many refugee- and immigrant societies they are pushed towards studying something that will allow them an income or a profession, so you see less people in the humanities and the arts, because it’s a less profitable path in general.

I’m focusing on these particular artists, because I think they are offering a different kind of process, where they use their style of their work to be acknowledged as artists in their own society, because they do really beautiful art work, beautiful paintings. It looks real. It’s not abstract or conceptual. You see things you can recognize, and you can also recognize the talent, and therefore if you recognize the talent, that legitimizes them as artists.

I don’t know how conscious they are of this choice, but I look at the path of these artists, and they all studied in a college in the North that also gives students a teaching certificate, so when you finish the degree, you can teach art in school, and that gives them a profession so the parents therefore allow them to do it.

It’s not just art, and I don’t know if, consciously or not, they recognize that in terms of showing their talent in a way that their society can appreciate, but then they won’t necessarily have to rebel against their families.

That’s the subversive move that they are doing. At the same time their paintings are full of criticism about their own society in a subtle way and you have to read the symbolism within it. Their work is forming gender-criticism against the patriarchy in the Palestinian society, so they are using the façade of the beautiful painting to be accepted but then also to criticize it.

In order to talk about their work, I am using post-colonial theory that establishing different kinds of liminal spaces or third spaces, where it is hard to separate the influences of the occupier on the occupied and vice versa.

I worked with three of them as part of my work at the gallery. I helped produce their exhibitions and catalogues, so I got exposed to their work through the gallery, and I also got to know them in person. I got to see their work next to [Palestinian] male artists that were in the exhibition at the same time, and I found that there is something that the women are doing that I find more interesting.

Clean

It’s been almost three years ago that I started noticing that and that I really found it compelling. I literally was thinking: Wow, this is so much more interesting as a way of producing art. So I think that it stuck with me for a while, and when I started studying here I didn’t know what I wanted to do, but I knew that I wanted to use my experience and my work at the gallery and to take advantage of the fact that I really got to know a lot of these people in person.

There is not a lot written about Palestinian art in terms of academic research. There are also very few Palestinian researchers, because, as I mentioned, most choose to go to fields that bring money. Of those who can afford it, they will go to be engineers, doctors, lawyers or just something that you can hold in your hand, and there are less people who go to fields within the humanities, which leaves a very difficult situation, because it leaves the writing of the culture in the hands of Jewish people.

The Israeli President Wife's visit, Umm el Fahem, 2015.

Even for me, it’s sometimes a difficult situation, because I have to justify for myself the reasons why I am writing about them. I have to clear it to myself – that my intentions are not just good, but I have to try to keep it clean in the sense that I’m not trying to take advantage or use my privilege in order to “empower” other women.

My grandparents are European; I’m half German and half Polish. Only my father was born here. My mother wasn’t born here.

Of course my personal history is interesting to me, but I feel like enough has been said about this part of the Jewish world.

Binary / Grey

I do think that we’re getting into more complicated territory, but I think that something in my personal history – in the fact that I’m a first or second-generation immigrant of people who had to leave everything behind and start a new, helps me be more humble when I am writing about minorities in Israel.

I grew up with a grandmother who never felt like she belonged here, because she was European. She didn’t come here because she wanted to. She was forced to come here because she didn’t have another choice.

I’m not interested, in any way, in comparing the two histories, but these are two narratives that have been in some kind of competition for the past 70 years (the Jewish narrative and the Palestinian narrative), and I think that there is something in the way that they [Palestinian women artists] don’t fight the system but kind of find a way to work within the system that I can personally really sympathize with.

There is always the complication of things that are not binary, and I think I have a really hard time with this sort of human need to put everything into two sides, this binary experience where it’s only about “your narrative or their narrative,” where you can either only support your personal story or 100% agree and sympathize with the other narrative. There is never an experience of middle ground, which usually reflects reality everywhere.

The grey area is what we eventually all experience but in terms of what we tell ourselves, we naturally want to be on one side, on one of the sides, so I think that’s how I relate to this topic I chose to write about.

I think that I’m bothered by the binary discourse that I’m forced to participate in and therefore, as an artist and now with my thesis, I’m trying to expose the binary apparatus and to suggest a “third space,” which allows for more than a single narrative and a single truth.

Installing the exhibition Venus Palestina, by Fatima Abu Roomi, Umm el Fahem Gallery, 2017

As for the artists that I am writing about, they do it almost as a way to survive. For them it’s only in order to get out and in order not to lose everything. I, on the other hand, don’t have to live like that because of my privileged position, but that is the place that interests me the most and that I feel I can operate within.

Moved

I live up North in Israel, and have lived abroad for eight years.

I lived two years in Amsterdam and six years in the US, where I received my undergraduate and graduate degrees.

My husband is American, and we moved to Israel to raise our kids. With all the difficulty, it feels that we can give them a better childhood here.

Though I have my degrees in fine art, I found myself working more in the administrative side of the art world. I got the job at the Umm el Fahem Gallery by chance, but it really created the right combination for me between ideology and production of art.

Something Greater

I have a vague fantasy of continuing to do a PhD, because now it’s just my Masters, so I can’t do much in terms of an academic career.

I have to first deal with finishing the thesis, but I am bringing up the idea of not doing it in Israel and maybe to go somewhere else to write it. Again, it has a lot to do with my topic and the relevance of doing it here rather than doing it outside of Israel, what I want to gain, but I’m pretty much drawn to the academic path.

I won’t say “no” if I get a great offer to work in a really good institution, but I have to say that I’m not going to work for just an art institution. I think I got really involved in the experience of art being part of something greater, so if it’s some sort of social, political thing, where art plays a bigger role, and it’s not just an art institution or an art venue, then yes.

It has to have another role in terms of working with the community, bringing difficult subjects to the front that you can’t otherwise really discuss, and then to process them through art, using it as a platform for discussion and dialogue.

Fatma Shanan, Two Girls Holding a Carpet, 2015, oil on canvas, 80/100 cm

Interview conducted on September 11, 2017 by Sarah Arnd Linder