HER STORY #58 - rawan

Jaffa

I was born and raised in Nazareth or to be more specific, in Jaffa of Nazareth [Yafa al-Naseriyye in Arabic]. It’s very near Nazareth, and it’s basically the Jaffa [reference to Jaffa next to Tel Aviv] of Nazareth.

That’s why it’s sometimes confusing for people, when I say that I work in Jaffa [in Tel Aviv]. People will say, “Ah, that’s very close [to Nazareth]!” And I respond, “No, it’s not. I’m not in that Jaffa. I’m in this one [in Tel Aviv].”

My family is from Ma’alul [a destroyed village near Nazareth]. It’s empty today. In 1948, they [Israeli army] destroyed 536 villages and my village was one of them.

They kicked the people out of Ma’alul, and they had to go somewhere, so they went to Nazareth. The first place that all the people came to had a church, and since the church was open they went there and with time they began buying land in Yafa al-Naseriyye.

When I lived in Yafa al-Naseriyye I went to school in Nazareth.

Haifa

Then I went to Haifa University to study Education and Sociology, and I also worked at the Haifa Municipality and at the community center [in Haifa] during my studies.

I was involved with a project called Open Apartment. Other students and I received scholarships, as well as an apartment (shared by four people), by working ten hours per week in the neighborhood. I had this scholarship for two years.

Very Far

I came to Jaffa of Tel Aviv to participate in a political tour of Jaffa [before actually moving here]. It was really interesting for me because I’m from Nazareth, and Jaffa [of Tel Aviv] is very far away from us—for the people of Nazareth. Mentally it’s far away.

It was after that tour that I understood that the situation here is very complicated.

Basically, what happened is that after 1948, when 536 [Palestinian] villages were destroyed, there was a military regime from 1948 until about 1964. People couldn’t go anywhere, meaning the people from Jaffa couldn’t go to Lyd [Lydda or Lod in Hebrew], or to Nazareth, or anywhere else, because they lived in a ghetto in Ajami [neighborhood in Jaffa]. That’s why the people from Jaffa stuck together, and they didn’t mix with other Palestinians from inside Israel.

The majority of Palestinians living in the North, including in Nazareth, could go from Nazareth to all the villages nearby, but Jaffa seemed very far because no one could go to Jaffa from 1948 until 1964.

What happened in Jaffa, because of the ghetto of Ajami was that people began using drugs and there was a lot of violence. You would hear of people getting shot every day, so people were also afraid to go there. That’s also the reason why it’s very far away [mentally] for us.

When I came here seven years ago and had my first political tour, I began to understand the whole political situation by being in Jaffa – also because it’s different than all the other Palestinian villages and cities.

Jews

When I came to work here in Jaffa, it was also the first time that I met with Jews for real, and I’m saying for real, because when I went to high school, and we met other Jewish students from other schools, the meetings were very shallow. Also, in Jaffa I got to meet with Mizrahi Jews [Jews of Middle Eastern descent] and not only European or Ashkenazi Jews as those that I had met in school. European or Ashkenazi Jews.

We had a dialogue meeting with them for only two days, so I felt like it wasn’t a real meeting.

When I studied in university, and there was tension, especially during wars, we [Palestinian students] would demonstrate in front of the university with our left-wing Jewish classmates, and next to us the right-wing Jewish students would demonstrate, and we didn’t have any dialogue. We just saw each other as enemies. I also didn’t talk to any Jews [on a deeper level] while studying there.

And in Nazareth I didn’t meet any Jews, because the whole population there is Palestinian. It’s true that there is Nazareth Illit [Jewish town overlooking the Arab city of Nazareth, founded in 1957], but when I go there the only interaction I have with Jews is “hi” and “how much does this cost?” It’s not really a dialogue.

When I came to Jaffa, I began working at Sadaka Reut [NGO] where we work with the [Arab and Jewish] youth and students to pursue social and political change as partners through a binational vision.

It was my first real meeting with Jews. All my life, I had worked with Palestinians, and a little bit with Jews at the community center in Haifa, but it wasn’t real.

It was also the first time that I had a dialogue with Jews about the conflict—where I just said what I felt, and they said what they felt, and I also began to understand their fear, not just my own. It’s a legitimate fear. I think it was the first time that I listened.

That’s why I now think that we have to work together, and we also have to talk about the issues.

Nasrallah

Where I worked in Haifa, which was the Wadi Gimal neighborhood [Arabic name of neighborhood called Ein Hayam in Hebrew in Haifa], the neighborhood was mixed, where 40% of the population was Jewish and 60% was Palestinian. I worked with the youth population, but I mostly worked with the Palestinians, and a few times with elderly Jewish people, but we didn’t talk about the conflict.

In 2006, during the [Second] Lebanon War, the Jews told the Palestinians in the neighborhood to leave the shelters. Hassan Nasrallah [Secretary General of Hezbollah in Lebanon] had told the Palestinians in Haifa that he would bomb Haifa and do even more than that. He told the Palestinians in Arabic to leave Haifa.

So the Palestinians just left, although they came back afterwards, but a lot of them left, because they thought it would turn into a big war.

The Jews [of the neighborhood] then told the Palestinians, “Hassan Nasrallah told you to go, and you’re not supposed to be here in the shelters, because we’re enemies. Nasrallah is an Arab, and he will bomb us. We don’t want you here in the shelters.” So they [Jews of neighborhood] really kicked us out [of the shelters].

After that [the war] people began talking about this. We hadn’t talked about politics before. We had just worked on women’s empowerment or empowerment of the people of the neighborhood. We just played with the kids and helped the neighborhood in terms of socio-economic problems.

That is when I told myself: I am not going to work in a place where we don’t talk politics because we face political issues. We face it every day, because every other year we have wars here, and look at everything that has happened in Gaza. We have to talk about that.

Arab Jews

When I came to Jaffa I had the first meeting with Jews, and they weren’t Ashkenazi. I got to meet Jews from Arab countries, which was a shock for me – to get to know Jews who are Arabs.

I hadn’t known anything about them, because in history classes in high school we only learned about Jews coming from Europe and about the Holocaust. No one mentioned the Jews from Arab countries.

Also, 20 years ago, all the people in the media were Ashkenazi only, and most people in the media still are Ashkenazi and not Mizrahi. Now we see more Mizrahi, Ethiopian, and Russian Jews, but it wasn’t there before. It’s also something that wasn’t talked about within Israeli society.

It was the first time that I met Jews who also listened to Umm Kulthum [internationally famous Egyptian singer, songwriter, and film actress] and who would also sing with her. That was very nice to know about, as well as the fact that many of them had also watched Egyptian films that were broadcast every Friday, which had started in the 70s.

For me, as a Palestinian, to know that there were Jews who also sat and watched these movies, was extraordinary.

I wanted to see these films because it connected me to the Arab world. I had Jordanian TV channels along with the Egyptian films [shown on Israeli TV], and it was the only thing that connected me to the Arab world.

At the same time, I found out that there were Jews who wanted to connect to their roots, and there were Jews who were talking about the same experiences that I had had.

What happened to the Arab Jews was that they [Israeli state] asked them not to speak in Arabic, only in Hebrew. This is the language. We are all the same, so don’t speak Arabic. Their family or their parents were ashamed of speaking Arabic, additionally because it wasn’t considered a good culture. The “good” culture was European, also in terms of music, so you weren’t really allowed to listen to Arabic music. That’s why they didn’t connect to their Arab roots.

Now we see that things have changed, which is very good, but it’s also because the Jews who came from the Arab world struggled very well within their communities.

Sadaka Reut / Community

At Sadaka Reut we work with youth and students, and we work on a uni-national and a bi-national level.

We have a Jewish co-director and a Palestinian co-director (who is me) and all the projects are coordinated by two coordinators, one Palestinian and one Jewish.

What we try to do at Sadaka Reut is to be activists in our own communities—above all to know what happened and what happens in our community. By this, I mean that first we want them [youth members of Sadaka Reut] to get to know their community, including the struggles and the problems faced by their community.

So, for example, if we are talking about a group in Tayibe [Arab city in central Israel] or Netanya [city in the Northern Central District of Israel], they have to know what happened in their communities first.

Palestinian Girls

We want them [youth members in Sadaka Reut] to be active, so they have to choose something to do to change things in society.

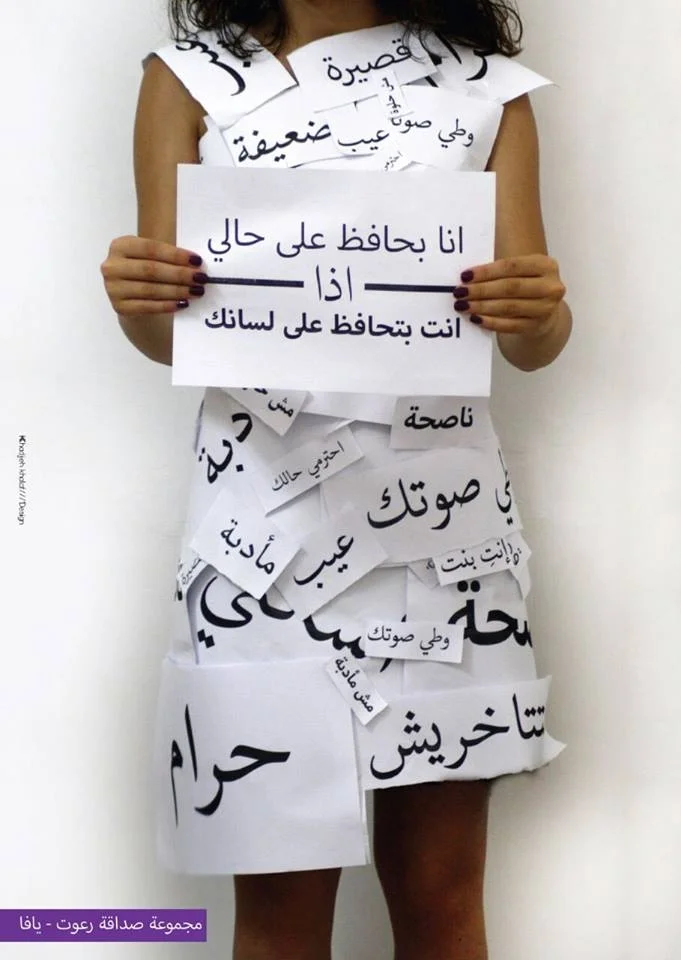

For example, there is a group in Jaffa made up exclusively of Palestinian girls, and they talked with a facilitator about what happens to them in the streets and how boys will tell them that they’re fat, or that they are not supposed to speak loudly, simply because they are girls.

So they created posters in an outline of a dress, covered with words of all the things they heard people say, such as “you’re fat.” It’s a dress made out of paper, so one of the group participants wore it. And they put posters all over Jaffa as well with stickers saying, “I will protect myself, and you will protect your mouth.”

People talked about [the campaign] on different media channels and all over social media.

Two years later, the same Palestinian girls talked about two issues: the discrimination and racism that they face from the Israeli community, and the other one within the Arab community. So they made another poster addressing the Israeli community, saying, “When I’m on the bus and I speak Arabic, I don’t feel safe” and another one for the Arab community saying, “When I go home from school, I don’t feel safe. You’re wrong, not me.”

Kiryat Shalom

One of the Jewish groups was from Kiryat Shalom [neighborhood in southern Tel Aviv], which is a Mizrahi neighborhood with socio-economic problems, and the municipality of Tel Aviv didn’t give Kiryat Shalom enough money. You see many differences between the streets of northern Tel Aviv, for example, and Kiryat Shalom.

On poster: "You don't see us! Tel Aviv Municipality: Kiryat Shalom needs light too"

They [inhabitants of Kiryat Shalom] also don’t have lights in the streets during the night, so they made posters addressed to the municipality. It said, “You couldn’t see us” with the picture of a street at night without lighting.

They went from house to house to collect signatures of the people who supported this campaign, and then they took the petition to the municipality.

Political

These are the kinds of things that they [Sadaka Reut groups] do on a uni-national level. They first get to know their own community and their community’s problems, because we believe that if you’re aware of them and know how to solve your community’s problems, you will also be able to do that on a higher level.

First they are supposed to do something in their community, and in the second year to do something on a bi-national level. For example, the group in Jaffa, who is composed of 16 members, half Palestinian and half Jewish, volunteer in one neighborhood in Jaffa for one year. For example, part of their work is to go to elementary schools and high schools together to help kids with their homework.

In addition to this, they also get to know the political situation, and talk about identity and different narratives. For example, in terms of Zionism, we want them to think about it in critical ways and not only to talk about Zionism in one way.

We talk about the history of the place, what happened here in 1948, what the regime did from 1948 until 1967 with the Jews, who came from the Arab world, and what happened to the Ethiopians. They also go to the Jordan Valley, Jerusalem, Jaffa, the north, to the destroyed [Palestinian] villages, and other places to gain a lot of knowledge, which they then can use for something.

Street Signs

Three years ago one of the Jewish groups [of Sadaka Reut] went on a political tour of Jaffa, and they saw that all the street signs had Hebrew names only, such as Sderot Yerushalayim. They all had names of only Jewish people, including Jewish people who had been to the army, or the names would be international, such as Michelangelo Street.

When they saw that, they decided to do a campaign aiming to put Arabic names on street signs to replace Olei Zion with Mahmoud Darwish [Palestinian poet and author].

They did this at night, because it’s basically vandalism – something they are not supposed to do. However, sometimes if you want to be an activist, you need to do things without [municipal] permission, because you wish to say something to the municipality.

So they did it, and the day after it was really nice. All the names were written in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, and they looked like the real signs, although they were just stickers.

The municipality kept it for three hours, and then they removed it, because the names were changed, which wasn’t legal.

But I remember how the day after people went around saying, “Yesterday this was Shivtei Israel [street] and not Naji al-Ali [Palestinian cartoonist].” An elderly [Palestinian] man actually told me, “For the last 65 years I haven’t felt a connection to Jaffa. Now I feel it.” It was really nice when he told me that.

Ma’alul

All of Ma’alul has been destroyed, apart from two churches, so in 1976, children of former inhabitants of Ma’alul asked someone from Ma’alul to draw the plan of the village, which is how we know what it looked like.

I’m not sure if it’s true, but we’ve been told that the meaning of Ma’alul is “door to the Galilee,” Jab il Jalil in Arabic, in a metaphorical way.

One of the people, who told us this were people Zochrot [Israeli nonprofit organization founded in 2002 with the aim is to promote awareness of the Palestinian Nakba] and I interviewed an elderly couple, who were from Ma’alul and still alive. We asked them about what life was like there, and what they remembered.

Until 2003 there were all sorts of animals inside the churches, such as cows. In 2003, the people from Ma’alul cleaned one of the churches – only one because one of the churches is Orthodox [Christian], and the other one is Catholic, and the people from Ma’alul are Catholic. Until 1946 they were Orthodox, but then there was a big fight among the people of Ma’alul, so they all converted to Catholicism and they built a new church.

Since the church’s renovation in 2003, every year we have a big celebration and a mass inside the church on the Second Day of Easter. It was a way for us to bring back all the people that fled Ma’alul, including my family, to celebrate there.

The mosque of Ma’alul hasn’t been renovated, because they [Israeli state] didn’t allow it. It was a way for them to create a divide between Christians and Muslims. In fact, during the war in 1948, almost all the churches were damaged, while all the mosques were completely destroyed.

I was just there on Saturday. When the weather is really nice, my friends and I go there. Instead of eating lunch at home, we’ll go to Ma’alul because it’s really nice to have a picnic next to the church, and then it’s empty [of people].

The church is closed, but some people have keys to it, such as my father. The church has toilets and you can make coffee inside.

Refugees / Identity

Ma’alul had 840 inhabitants, and today these families include 7,000 people.

There is a map and pictures of what Ma’alul looked like before the Nakbe, and we have drawn up maps of how we would like for it to look in the future.

We are lucky because Ma’alul is empty, and we wouldn’t want to kick anyone out of their houses, so we are thinking of how we could bring all the refugees back.

This is all a very important part of my life, of my identity – the fact that I’m also recognized here as a refugee. I also think it’s the reason why I’m very connected to my Palestinian identity.

All of my family has always been very involved with Ma’alul, and they always talked about it. My grandfather and my grandmother both told me stories about how life was in Ma’alul.

Women Of Ma’alul

The women of Ma’alul are also very strong.

I think it has to do with the fact that they became refugees in 1948, so they had to be strong. One day you had a home, and the next day you had nothing.

And they [women of Ma’alul] know what they want and are responsible for a lot of things in their homes. For example, my grandmother was the boss [in the household], just as her mother had been.

Her mother died ten years ago at the age of 100. Her name was Salma. She is my mother’s grandmother. She had tattoos on her body, but I have no idea why. I remember her being a very, very strong woman.

Daughter Of Jasmin

On the other hand, I recall that when I visited her, she would often ask me, “Who are your parents?” We were such a big family, so she couldn’t always remember everyone, and I would tell her, “I’m Jasmin’s daughter.” To this she answered, “No, you’re not Jasmin’s daughter. You’re Elias’ daughter.” She was my mother’s grandmother, but she would still refer to me being connected to my father’s name and not my mother’s name.

That was very interesting for me, but I would keep insisting on being Jasmin’s daughter. It made me upset too, and ever since then, questions of women and gender have been on my mind a lot. That’s also why I volunteer at Women Against Violence in Nazareth, and why I volunteer at their 1202 hotline.

Clean

It’s not easy to be a Palestinian woman. You have issues inside of your community and also within the Jewish community.

One day, seven years ago, I was in my neighborhood in Yafa al-Naseriyye and I told my parents, “The neighborhood is not clean. People just eat and throw away the trash in the streets. Let’s plan a day, where we [everyone in the neighborhood] clean the neighborhood.” They told me that no one would come, but I insisted on doing something about it.

I wanted to do a volunteer day, and I remember that my uncle told me, “I’m not going to do anything. It’s not my business. The children are supposed to do this – not us, the elderly.” To this I answered, “Okay” and then I invited all the people from the neighborhood for a volunteer day.

I went to everyone’s home in the neighborhood, and a meeting was set to take place at my parents’ house. I also invited the mayor, who came along with many others.

Women came as well, and I realized that they came because I was there and had invited them, because if a man had organized this, they would not have felt comfortable showing up.

My uncle and my father just looked at me and said, “Wow, people came.” People would thank my father for hosting them and for having them in their house. My father was very proud, but to tease him, I told him, “Just remember that I invited all of them!”

A week following the meeting the cleaning day took place. The municipality had even given us a lot of cleaning products.

It was all supposed to start at seven in the morning, but already at 6:30a.m. people were at my parents’ house and were asking where Rawan was.

The whole neighborhood, as well as different media channels, knew my name, and the funny thing was that my uncle and my dad were the first two people who started working. I remember that at the end of the cleaning day, my father told me, “I’m still very surprised that all the people came here just because you said it.” And he meant that this was unusual for women, since the men are the ones more involved with politics—which is also the case on the Jewish side.

Another uncle from my mother’s side told everyone, “She’s my niece! I’m very proud. Yes, she’s my niece!”

Three months later, I organized elections so that there could be a neighborhood committee. Today, there are also women on the committee.

This was the first time in Yafa al-Naseriyye that they saw a young woman as a leader, and I think it was because women were just there, and feminism wasn’t mentioned. I just did it.

Mitchab’rot

In Arabic and Hebrew, unlike in English, you have the masculine and feminine forms. You can say mitchab’rim [“connecting” in Hebrew, masculine, plural] or mitchab’rot [“connecting” in Hebrew, feminine, plural].

Sometimes, when I’ve sat with political activists, I have said mitchab’rim, and some women have asked me to say mitchab’rot instead.

I don’t believe in that. If you know me, you will know that in my daily life I’m a feminist. This is my life, so you don’t have to focus on the spoken word and to correct me like this when I talk. Don’t correct me, especially when I talk – that’s not very feminist to do either.

In some of the groups that I take part in, these are issues that will come up, and some will insist on using the feminine form of words. What is important for me is not only to apply feminism to words but also to behavior.

Only In Hebrew

I was in a feminist meeting the whole day today, where members from different organizations participated and talked about fighting racism. I sat with one Jewish woman and two Palestinian women.

At some point, we [the other Palestinian women and the interviewee] spoke in Arabic between ourselves, and then she [Jewish woman] told me, “For next time I would like to ask you not to speak Arabic when we meet.—only in Hebrew.” I told her, “When we speak in Arabic, we discuss personal things, not related to the meetings. And you’re asking me not to speak in Arabic just for you to understand, and you don’t want to learn my language.” It turned into a big discussion within the whole group.

I was shocked. I was really shocked, and I told her that I was upset and angry, and told her that I didn’t know what she was doing here if she was telling me this. I also told her that Hebrew is my second language and Arabic my mother tongue, and sometimes it’s hard for us to understand things in Hebrew, so we switch to Arabic, which is fine.

She told me that her daughter is married to an American, so when they get together [Jewish woman, daughter and husband] they speak in English. Even if she talks with her daughter, she will speak in English, because it’s polite. I told her, “Excuse me, but there is no occupation between you and your daughter’s husband. There is no discrimination between the two of you, so if it means that I’m not polite, well okay then, but it has nothing to do with each other. It’s very, very political.”

To this she added that she has Palestinian friends, which I found ridiculous. I found it okay for her to feel uncomfortable [with interviewee and two other Palestinian women], because for the last two days we had all spoken in Hebrew.

My Struggle

At first, when I really understood what had happened in Ma’alul in 1948 and I heard all the stories, I got angry and frustrated, and I felt like a victim.

I felt like this around the age of 18-19. I had known about it [destruction of Ma’alul] before, but the Second Intifada took place when I was 18, and that was all a big shock for me because that’s when Palestinian citizens were killed by the police, and I began to make the connection between the two things.

At the same time I didn’t speak any Hebrew at all, only Arabic, and I perceived all Jews as my enemies. And while this was happening, my grandmother got very sick with Alzheimer’s, and the only memory she has was of the Jews kicking them [inhabitants of Ma’alul] out of Ma’alul. So this is what I heard all the time.

I was very Palestinian and very connected to the [Palestinian] flag. I would wear the keffiyeh a lot, and I just wanted everyone to know that I was Palestinian.

This is the process that every Palestinian here in Israel has to go through – to feel that we became victims—not because we were bad or not good enough, but just for being Arab—and then to become very nationalist, and later to take it to another step, which is to struggle and to be active.

I know what happened to my family in 1948. I know about the whole struggle, and what is important to me is to fix the situation, but not because I feel I’m a victim. I know that we, as Palestinians, are victims, but what gives me the motivation is my belief in the struggle – in my struggle to bring back all the refugees through Palestinian and Jewish binational partnerships.

This is my struggle. This is why I’m active, and this is why I’m doing what I’m doing.

Life

Usually most of the memories from Ma’alul that are spoken about are sad, but the Second Day of Easter is the only occasion when we have a celebration.

Usually when you go on a political tour of destroyed villages, you meet the people [who lived there], and who will tell you what happened in 1948. They will tell you about all the bad things and the sadness, but on this day [second day of Easter] you get to feel the happiness, and the people coming back to Ma’alul. It’s a very good feeling.

Many times when we talked about the Nakbe, we basically only talk about the Nakbe itself and what happened after. We don’t talk about what was before, and sometimes people just need to know that people lived here, how it was here, how the relations between people were, and how people loved each other.

That’s also what made me change my perspective on this. Now I also try to talk about the good things there were before.

They try to say that there is no [Palestinian] nation here and that no one was here [before 1948], but there was life.

Interview conducted on May 6, 2017 by Sarah Arnd Linder